Chapters and verses (pt. 1)

Two prominent features in modern Bible translations are the chapters and verses. People often ask me how they got there. Some think they were there from the beginning but they weren’t. When Paul wrote the book of Romans, he didn’t divide it into sixteen chapters.

One of the things we hoped to do with The Voice project was to help people understand that the Bible is not actually a single book. It is a veritable library of books, sixty-six in all, written over a period of more than 1000 years. The current configuration of the Bible didn’t just happen. The order of the books and the collection itself represents a driving theological force which Christians believe was orchestrated by the Holy Spirit. But what about the chapters and verses?

When the many authors, co-authors, and secretaries wrote their respective books, they didn’t include chapters and verses. They composed their books from beginning to end without putting in breaks. Now this doesn’t mean there were not structures in place which became breaks. For example, the book of Psalms is composed of 150 hymns which had an introduction or superscription describing who the author was or to whom it was dedicated along with other directions for how it was to be chanted or sung. Clearly, these were breaks but they weren’t the same as our chapters and verses. Likewise, the book of Lamentations is written in an acrostic style which is discernible only in the original language (Hebrew). The Voice translation tries to replicate that acrostic style in an English translation. So clearly these superscriptions and acrostic forms provide structure, but structure is not the same as chapters and verses.

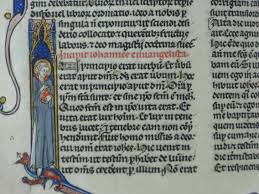

There were early attempts to provide a convenient structure to the books of the Bible but the one we use today goes back to the 13th century. A fellow named Stephen Langton divided the Bible into chapters in 1227. He was a professor at the University of Paris. Later he would go on to become the Archbishop of Canterbury.

The verses we use today were added centuries later by a French printer named Robert Estienne. In 1551 he divided the Greek New Testament into verses. Since the official Bible of the Catholic Church in those days was the Vulgate—a Latin translation—the first programmatic use of chapters and verses for the whole Bible was published in 1555. The first English New Testament to make use of these chapters and verses was a translation by William Whittingham (1557). The first English full Bible to use chapters and verses was the Geneva Bible (1560). Since then Bible translators and publishers have adopted and standardized the use of chapters and verses. Some editions of the Bible have been published without them, for example, Richard Moulton’s edition The Modern Reader’s Bible (1907).

Chapters and verses are handy because they make it possible for people to find the same book, chapter, and verse for public reading or study. Otherwise, we’d have to say, “Go to the passage where Luke tells us the early Christians were devoting themselves to the teachings of Jesus’ apostles.” Now which book would you go to, and which part of the book would you find that passage in? The answer is Acts 2:42. Much easier, right?

While chapters and verses are a handy way of indicating specific places in the Scriptures, they sometimes cause us to disregard the narrative flow of a text or in a worse case scenario misread it altogether. We will consider these in the next couple of posts.

You must be logged in to post a comment.