“’Jerusalem’ in The Gabriel Revelation and the Revelation of John”

“’Jerusalem’ in The Gabriel Revelation and the Revelation of John”

by David B. Capes

—this is an early version of an article published in Hazon Gabriel: New Readings of the Gabriel Revelation, edited by Matthias Henze

When the scribe incised the guidelines into the soft limestone and began copying the text we know today as The Gabriel Revelation, Jerusalem had been the center of Jewish life, hope, and imagination for centuries. More than half a millennium had passed since Ezekiel described the holy city as the center of the world (Ezek 5.5; cf. 38.12), a theme picked up and elaborated by other writers (1 Enoch 26.1; Jub 8.11, 19).[1] When David captured the Jebusite settlement (2 Sam 5.6-10) and moved the ark of the covenant there, he set in motion a process whereby his capital came to be regarded as the nexus of earthly and heavenly power, the locus of God’s final, definitive actions to redeem God’s people. Even when it was attacked, destroyed or controlled by foreigners, Jewish imagination did not relinquish the hopes fixed on this city. As Carey Newman writes, “ideal figurations of this holy city, this Zion, became stock symbols for Jewish worship and eschatology.”[2]

Around the turn of the millennium—when The Gabriel Revelation was inscribed—these ideal figurations were expressed in a variety of ways in Jewish and Christian literature. First, some Jews envisaged a day when the earthly Jerusalem would be restored and purified. Second Baruch, for example, describes a time when the Mighty One will shake the entire creation and the building of Zion will be razed in order to be rebuilt, “renewed in glory” and “perfected into eternity” (2 Bar 32.2-4; cf. Tob 13.9-18; Test Dan 5.12).[3] Second, other Jews and Christians situated the perfect Jerusalem in heaven and considered it the place to which God’s covenant people will ascend. In contrasting the two covenants, Heb 12.22 portrays true believers as arriving at Mt. Zion, the city of God, the new Jerusalem in the company of angels, God, and Jesus, the mediator of a new covenant (cf. 2 Bar 4.1-7; 4 Ezra 8.52; 4 Bar 5.35). Third, yet others looked for a new, perfect Jerusalem to descend from heaven to earth some time in the future (Rev 3.12; chs. 21—22; 4 Ezra 7.26; 10.25-54; 13.36).[4]

Among the Dead Sea Scrolls the covenanters held “three distinct but related notions”[5] of Jerusalem. On the one hand, the community of the faithful—when properly disciplined—is described metaphorically as “a holy house” where “the offering of the lips” is sufficient and no burnt offerings or sacrifices are required (1QS 9.3-6; cf. 4Q164 1-7; 11QMelch 2.23-34).[6] This conviction existed without contradiction with two other, related notions: the covenanters believed (a) God wanted them to establish a temple and maintain its purity and sacrifices “until the day of creation” and (b) God would one day build the final temple, an eternal temple (11QTemple 29.6-10; cf. 4QFlor [4Q174] 1.1-1). The majority of references to Jerusalem in the scrolls depict the holy city in these idealistic terms; however, the real situation on the ground at the time when the scrolls were written shows deep divisions over issues of purity and scriptural interpretation.[7] The Habakkuk pesher (1QpHab 12.7-9) complains that Jerusalem had been corrupted and the temple defiled by the Wicked priest. Other scrolls protest that God’s people will suffer because Jerusalem is ruled by arrogant men who reject the Law (4QIsaiah Pesherb 2.1-9) and look for easy interpretations (4QIsaiah Pesherc 23.ii.10-12; 4QpNah 3-4.iii.6-7). These tensions provoked a variety of reactions but, perhaps more than anything, a longing for a New Jerusalem.

The Gabriel Revelation provides further evidence that Jerusalem is the one place on earth that captured the Jewish imagination. The holy city figures prominently in this brief, fragmentary prophecy that originated likely before or at the beginning of the first century CE.[8] This essay explores the role of Jerusalem in this prophecy and the Revelation of John. It suggests that these prophecies portray what appear to be different versions of an accepted apocalyptic scenario regarding Jerusalem and its future. While these texts share much in common, there are some important differences as we will see. In addition, Revelation’s account of Jerusalem in ch. 11 may provide some help in interpreting particular aspects of The Gabriel Revelation.

Jerusalem in the Gabriel Revelation

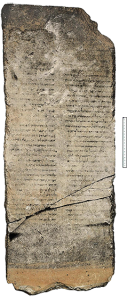

According to Yardeni, Elitzur and Knohl the word “Jerusalem” occurs seven times among the legible lines ofThe Gabriel Revelation inscription (lines 12, 14, 27, 33, 36, 39, 57).[9] Qimron and Yuditsky restore the text to suggest three other occurrences of the word (lines 32, 60, 66).[10] So the extant part of the inscription contains seven to ten references to the holy city. References to David (“my servant David” in line 16 and “David, the servant of YHWH” in line 72) may indicate that the people who read and were influenced by The Gabriel Revelation supported the Davidic dynasty, which, may in turn, reinforce Jerusalem’s importance in this prophecy. [11]

Knohl argues that The Gabriel Revelation focuses on two themes. Our concern here initially is with the first:

The first half [of the inscription] describes an eschatological war, in which the nations of the world besiege Jerusalem, expelling its residents from the city. God, in response, sends ‘My servant David’ to ask Ephraim—the Messiah son of Joseph—to place a ‘sign,’ presumably heralding the coming redemption. The text goes on to describe the vanquishing of the Antichrist and its forces of evil. God Himself appears together with His angels to defeat the enemies.[12]

Knohl attempts to situate the text in the aftermath of Rome’s crushing defeat of Jerusalem and Judea prior to the turn of the millennium. In the political vacuum left by Herod’s death insurgents revolted against Rome’s domination and were soundly defeated when thousands were killed, cities and villages were destroyed and the temple burned.[13] According to Knohl, those who composed The Gabriel Revelation desired to raise the spirits of God’s faithful and offer them hope that redemption was indeed at hand. Despite what they had seen and experienced, God was still in control and would soon judge his enemies.

In the first column of the revelation God appears to address directly a human being but the extant text does not identify the seer. In what can be read, a dialogue takes place in which God does most of the talking.[14] The “God of Hosts” begins to tell of Jerusalem and her greatness[es] (בגדלות, line 12). Knohl remarks that this line provides an introduction to “the miraculous salvation of Jerusalem.”[15] One day “all the nations” (כול הגאים, line 13) will surround and besiege Jerusalem in a great eschatological battle. Though he calls it doubtful, Knohl reconstructs the text at the end of that line “and from it are exi[led],” partly on the strength of the intertextual play between The Gabriel Revelation and Zech 14.2. Clearer references to exile in lines 37-39 may well confirm his suspicions. On a strictly human level, the situation seems dire, but as the prophecy unfolds it becomes clear that deliverance is not far away. A sign of redemption is set (lines 16-17) and the Lord of Hosts, the God of Israel, announces that evil will be broken before righteousness (lines 19-21). Qimron and Yuditsky suggest that lines 17-19 be read: “Thus said [Y]HWH of Hosts, the God of Israel: My son, I have a new testament for Israel, by three days you shall know.” This restoration seems consistent with the rest of the prophecy and provides a more satisfying reading than either Knohl’s or Yardeni’s and Elitzur’s. If correct, it clearly reflects the “new covenant” language of Jeremiah (31.31). Six centuries earlier Jeremiah announced the terrible news of God’s coming judgment against Israel and Jerusalem. The holy city, once thought invincible, was destined for destruction according to the prophet. Yet even as God threatened to punish Israel for her sins, he promised to restore the fortunes of Judah and make Jerusalem again a place of joy (33.6-9). Jeremiah’s prophecy of destruction and “new covenant” may well be imprinted on this turn-of-the-millennium prophecy. However, God promises to shake the heavens and earth “in a little while” (lines 24-25; cf. Haggai 2.6) and to reveal his glory (כבוד, line 25).

There seems little doubt that Zechariah 14 and Haggai 2 provide scriptural inspiration for the future of Jerusalem envisioned in this revelation. The closing chapter of Zechariah’s prophecy presents a broad description of an eschatological battle in which “all the nations” gather against Jerusalem, overthrow the city, loot the houses, rape the women and carry half of the citizens into exile (14.2). But when all seems lost, the Lord goes forth to fight against the nations. As with other theophanies, the divine appearance disrupts nature shaking the earth and carving out a valley toward the east. As for those who survived and remained in Jerusalem after the initial attack, they will leave the city and escape the coming battle. The Lord arrives and “all the holy ones”—a reference to the angelic army—are with him (Zech 14.5). Plagues fall upon those who have waged war against Jerusalem; even the animals in their camps succumb to sickness and disease (Zech 14.12-15). In Zechariah’s idyllic vision living waters flow from Jerusalem to the east and west as the holy city sits high above the surrounding plains. The victory of God in this final war causes the world to recognize the one, true God. Zechariah writes: “The Lord will become king over all the earth; on that day the Lord will be one and his name one” (Zech 14.9). Thereafter Jerusalem, the holy city, will be safe and inhabited once again by God’s people. Never again will she be threatened with destruction (Zech 14.10-11). In the years that follow all the nations that once attacked her will stream up her slopes to worship the King, the Lord of Hosts, and to keep the feast of Sukkoth. Those who do not will face plagues and punishments (Zech 14.16-19). Zechariah’s eschatological vision appears to provide the basic outline for the future role of Jerusalem in The Gabriel Revelation: (a) all nations gather to battle against Jerusalem (lines 13-16); (b) key citizens are taken into exile; (c) the Lord and his angelic army arrive to fight for his people and their city (lines 24-31); and (c) Jerusalem is miraculously delivered. Zechariah’s vision has to do with the earthly Jerusalem, judged, restored and protected by God. Whereas God had allowed Jerusalem to fall to imperial forces in the past, in the future God would repulse any attack and defeat his enemies soundly.

Haggai’s prophecy as well shaped the eschatological expectation regarding Jerusalem in The Gabriel Revelation. The sixth-century prophet Haggai uttered his message in the shadows of an inglorious Jerusalem. When Cyrus issued his decree allowing the exiles to return home, he encouraged them to rebuild the temple (Ezra 1.1-4); but nearly twenty years later, little progress had been made. So Haggai addressed Zerubbabel the governor and Joshua the high priest to take the lead in rebuilding God’s house. Not only would this momentous act unite a fractured people and bring prosperity back to the land, but it may also issue in the messianic age (Haggai 2.20-23). Haggai grounded the future work of rebuilding the temple in God’s promise made in the distant past when Israel came out of Egypt: “My spirit abides among you; do not fear” (Hag 2.5; cf. Exod 13.21-22; 14.19-20). He continues (Hag 2.6-7, NRSV):

For thus says the Lord of hosts: Once again, in a little while, I will shake the heavens and the earth and the sea and the dry land, and I will shake all the nations, so that the treasure of all nations shall come, and I will fill this house with splendor [or glory = כבוֺד], says the Lord of hosts.

The phrase “once again” recalls how God came in power to Mt. Sinai (Exod 19.16-25) and reflects a new Exodus perspective.[16] In the oracle God promises to shake the heavens, earth, sea, and dry land—the first realms of God’s creative actions (Gen 1.1-13). The shaking of the heavens and earth is clearly theophanic: YHWH appears and the earth shakes. Indeed this future event (“in a little while”) is both imminent and cosmic in scope. All of creation and those who inhabit it will be affected. Therefore, God will shake the nations and they will in turn bring their precious, natural resources to Jerusalem to rebuild and refurbish the temple (Isa 60.5; 61.6; 66.20). The material “glory” of the nations reflects the divine “glory” that will fill God’s new house one day so that Solomon’s temple will not “out-glory” Zerubbabel’s. The prophecy ends: “and in this place [the new temple] I will give peace [שׁלוֺם], says the Lord of Hosts” (2.9).

Lines 24-25 of The Gabriel Revelation echo Haggai’s prophecy. The reference to God’s “place” at the beginning of line 24 may well refer to the temple or Jerusalem.[17] If so we may surmise that the oracle proceeds from Jerusalem. God promises: “In a little while, I will shake . . . the heavens and the earth.” Here the shaking of the heavens and the earth is a prelude to the arrival of glory. The juxtaposition of the shaking the heavens and earth and the arrival of glory depends on Haggai’s prophecy concerning the future of Jerusalem and an eschatological age anchored by a glory-filled temple. As the prophecy unfolds, God’s glory is associated with seven chariots at the gate of Jerusalem and gates of Judea.[18] Although the text is fragmentary, this appears to refer to angels descending on chariots to wage war against the enemies of Jerusalem.[19] The appearance of Michael (line 28) suggests he leads the angelic hosts into battle.

Qimron and Yuditzsky restore line 32 to read: “ . . . [Je]rusalem [shall be] as in early times. . . .” They take the phrase “as in early times” to refer to the tree in line 31, symbolizing “rest and longevity” (cf. Isa 65.22; Am 9.11). This suggestion seems plausible and clearly comports with the theme of Jerusalem’s restoration. The Jerusalem to come will become as Jerusalem was in the days of old when heroes like David, God’s servant, lived. Line 33 follows with another reference to Jerusalem and her greatness (cf. line 12).

The references to exile (גלות) in lines 37-39, according to Yardeni and Elitzur, suggest the author and his community were forced out of Jerusalem and made to live in exile.[20] If so, then The Gabriel Revelation would be the kind of apocalyptic text which provided consolation to a defeated, humiliated, marginalized people. Exile from Jerusalem may well provide some of the historical backdrop, but we should also note that exile serves as an important, generative theme from Zechariah’s vision of Jerusalem and her future. Since Zechariah’s vision shaped this apocalypse, exile may be more of a potential threat to this community rather than its current reality.[21]

Fewer references to Jerusalem are found in what remains of the second column of the inscription. The clearest line is: סתום דם טבחי ירושׂלם כי אמר יהוה צבא[ות]. While the text is clear, its meaning is not. Yardeni and Elitzur suggest the phrase דם טבחי ירושׂלם refers to the sacrifices made in Jerusalem. Though they regard it is unclear, they suggest that satum (סתום) be read as a reference to a temporary interruption or interlude of the sacrifices at the Jerusalem temple.[22] Knohl, however, seems more confident that it refers to the bloody massacre of Jerusalem’s slain citizens. He bases this on subsequent references to “the blood of those slain” (line 67) and to the resurrection (line 80).[23] Furthermore, he translates satum (סתום) over against Daniel’s prophecy (ch. 8) and renders it: “Seal up the blood of the slaughtered of Jerusalem.” In other words the seer is urged to suppress the prophecy regarding those who will be massacred in Jerusalem when the Gentiles lay siege to the city.

Qimron and Yuditsky restore lines 66-67 as follows: “[Je]rusalem saying: (only) on You we rely, [not on]/flesh (and) not on man. This is the chariot . . . ” Neither Yardeni, Elitzur or Knohl restore Jerusalem at the beginning of line 66. Instead, they read the word “peace.” Qimron and Yuditzky restore the text based on the potential influence of Jer 17.5-8, a prophetic oracle that pronounces a curse on all who put their trust in mortals and fleshly strength and a blessing on those who trust in the Lord. If “Jerusalem” is correct in line 66, we may have a situation in which the faithful survivors or martyrs the nations’ attack on Jerusalem express their faith in the one who rescued them.

Given the fragmentary nature of the inscription, any reconstruction or interpretation of Jerusalem’s place in The Gabriel Revelation is necessarily provisional. Until further evidence can be brought to bear on this text to fill in vacant lines, we may never know the exact nature of this prophecy. Still enough remains to begin to sketch out a few contingent conclusions. Inspired by earlier apocalypses and prophecies (Zechariah, Daniel, Jeremiah, Haggai, and possibly others), the community of The Gabriel Revelation is told that a great eschatological war is coming that pits the nations of the world and their military might against Jerusalem and her faithful. When the nations arrive, they surround Jerusalem. In the attack many of the faithful will be slaughtered and Jerusalem’s key citizens will be taken into exile. However, a sign of redemption will be given (in Jerusalem ?) and God promises that evil will be broken by righteousness and the “wicked branch” will be exposed (cf. 2 Thess 2.3-12).[24] Jeremiah’s vision of a new covenant is in the process of being fulfilled in their midst. As the battle rages, the Lord arrives and the heavens and the earth quake in his presence. Divine glory eclipses the might and power of the nations as holy angels join the battle led by Michael, the archangel. In the end heaven and earth come together in the miraculous deliverance of Jerusalem, and she is restored to her former glory. “The place of David, the servant of the Lord” (line 72) is once again secure and will be for all time. The faithful remnant returns from exile and declares absolute faith in the one, true God. And the God who once promised to show steadfast love to the thousands who love him and keep his commandments (Exod 20.6) has proven once again to be faithful to his covenant (lines 68, 74).

The eschatological figuration of Jerusalem in The Gabriel Revelation is heavily dependent on images and prophecies found in the Hebrew scriptures. It is clearly a this-worldly Jerusalem even though heaven comes in power to redeem her. Absent here is any reference to a heavenly Jerusalem—as the home of true believers—or a new Jerusalem that comes down out of heaven to earth. Likewise there is no reference to the current community as somehow embodying Jerusalem or its temple as we see among the Dead Sea Scrolls or the New Testament (e.g., 1 Cor 3.16-17; 6.19-20

Jerusalem in the Revelation of John

As one writer put it, “the plot of Revelation can be read as the tale of two cities—the new and heavenly Jerusalem and the corrupt and sinful Babylon.”[25] Babylon the great, of course, is destined for destruction (Rev 14.8). The cryptic city is metaphorically portrayed as a woman donning royal garb and bearing blasphemous names (Rev 17.1-4). She is described as “Babylon the great, the mother of whores and the earth’s abominations” (Rev 17.5).[26] When the angelic guide escorts John into the wilderness to see her, she is drunk with the blood of the saints and the martyrs of Jesus (Rev 17.6). Tragically, her influence has extended throughout the world but her destiny—and the destiny of the world for that matter—is soon to change as the vision reveals God’s judgment falling swiftly (ch. 18). In a single day plagues will descend on her and she will be burned with fire (18.9). In a single hour her judgment comes (18.10). Though her allies mourn her destruction, heaven erupts in praise when God avenges the blood of his servants (Rev 19.1-4).

Within the prophetic narrative of Revelation, both the character and destiny of Jerusalem, the holy city, are far different than Babylon’s. The first reference to Jerusalem occurs in the letter to the church in Philadelphia (3.12): “I will make the victor a pillar in the temple of my God and he shall never again have to leave it and I will write the name of my God upon him and the name of the city of my God, the new Jerusalem which comes down out of heaven from my God, and my own new name.” The promises made to the Philadelphia faithful by the risen Jesus[27] situate them as a permanent feature in God’s final temple. Never again will they be separated from the beloved city and its temple; never again will exile be a real threat. Likewise, the names they bear indicate an abiding relationship with God and the revealer and lasting citizenship in the new Jerusalem. These promises are clearly eschatological and foreshadow the descent of the new Jerusalem from heaven to earth (Revelation 21—22). They help the persecuted minority in Asia Minor anticipate the kind of future they will experience if they stay true to the faith.[28]

Before the glorious new Jerusalem arrives, however, the earthly Jerusalem—like Babylon—must endure a time of judgment. John is given a measuring rod like a staff and told to measure the temple, the altar, and those who worship there.[29] [w1] Yet he is warned not to measure the court outside the temple, because it is given over to the nations (e{qnesin) who will trample the holy city underfoot for 42 months (Rev 11.1-2). No reason is offered as to why Jerusalem must suffer this disaster, but it is clear from what follows that God will not abandon Jerusalem forever and will indeed restore her. Two witnesses appear and prophesy powerfully for 1260 days (=42 months). When their work is finished, they are killed by the beast that ascends from the abyss. Their bodies lie unburied in “the great city which is called prophetically (pneumatikw“~) Sodom and Egypt, where their Lord was also crucified” (Rev. 11.8). These prophetic descriptions of Jerusalem as “Sodom” and “Egypt” and “where their Lord was also crucified” do not provide a reason for the judgment. Still the association with such infamous places suggests Jerusalem itself has been co-opted and corrupted by powerful, foul forces. Yet judgment and death are not the final word; their bodies do not lie like dung in the streets. After three and one-half days of their enemies’ celebrations, the breath of God enters them and they stand to their feet to the dread of all those who rejoiced over their demise. Their complete vindication is assured when a heavenly voice calls them to come up to heaven and the city is rocked by an earthquake (Rev 11.9-13).

A similar account regarding Jerusalem’s fate is found in Revelation 20. At an appointed time “the dragon, the serpent of old, who is the Devil and the Satan” will be locked up in the abyss for 1000 years (20.1-3). When the 1000 years have ended, the Devil will be released from the pit and go about deceiving the nations and gathering them for battle. The enemies of God and his people surround “the camp of the saints and the beloved city [Jerusalem]” (20.9). But even before the battle begins, it seems, the fire of heaven falls and consumes them; then the Devil is seized and thrown into the lake of fire and sulfur for an eternity of torment (20.7-10). This visionary episode of the nations’ attack on Jerusalem recapitulates the earlier account and intensifies it. It reveals the true power behind the scenes on earth (the Satan) and the impulse that drives powerful nations to line-up against Jerusalem. Likewise, it shows how quickly and definitively heaven responds to the threat. In this episode there are no martyrs, no exiles, and no long, drawn out battles; instead there is heaven’s swift, powerful response to the peril.

The prophet refers to the heavenly Jerusalem in an interlude of three visions (14.1-20) intended to provide comfort to the church as she faces persecution. The seer looks to see the Lamb standing on Mt. Zion in the company of 144,000 who have his name and his Father’s name written on their foreheads. John listens as they sing a new song—a song only the redeemed can learn (cf. Rev 5.8-10)—before the throne and heavenly creatures. The number 144,000 is a symbolic number representing the faithful of all generations. Although the word “Jerusalem” does not occur in these verses, the association of Mt. Zion with Jerusalem is unmistakable. The fact that this scene takes place before the throne, elders, and four living creatures suggests that John refers to the heavenly Jerusalem, for the new Jerusalem has yet to come down from heaven to earth (Revelation 21—22; cf. Heb 12.22).

The longest and most sustained treatment of Jerusalem in the Revelation comes in the final chapters. The new Jerusalem foreshadowed in Rev 3.12 becomes a reality following a great battle between the kings of the earth (Rev 16.12-16) and heavenly armies led by a rider on a white horse who bears the name “The Word of God” (Rev 19.11-21). The battle is swift and decisive. Satan and his minions are soundly defeated. The dead are raised to life and death itself is consumed in the lake of fire (Revelation 20). It is at this point in the storied prophecy that the holy city, the new Jerusalem appears, coming down out of heaven from God. In contrast to the harlot Babylon, she is described as a beautiful bride ready to meet her husband. The new Jerusalem experiences the unmediated presence of God that chases away sorrow, tears, and death. In the language of the Zion tradition,[30] the new Jerusalem is situated on a great, high mountain (Rev 21.10) and the glory of God radiates from it. Revelation de-emphasizes the temple in favor of the city itself. No temple is found there because the eschatological gathering of the faithful constitutes the temple (cf. 1 Cor 3.16-17). As Rev 3.12 foreshadowed, God’s faithful become pillars in the new Jerusalem and the heavenly city itself becomes the temple. This is perhaps why the city is described as a perfect cube 1,500 miles in length, width, and height (Rev 21.15-16). As Collins notes, the cube shape suggests that the city “plays the role of the holy of holies of the temple of Solomon” (cf. 1 Kings 6.19-20).[31]

As John’s story draws to a close, the angel shows him “the river of the water of life” that proceeds from the throne of God and the Lamb (22.1) and the tree of life. John’s language here clearly reflects biblical imagery associated with a newly restored temple and the holy city, the new Jerusalem, as a new Eden.[32] In Ezekiel’s vision of the restored temple a sacred river runs beneath the threshold of the temple’s entrance, flowing east to the Arabah, growing deeper until it becomes a mighty river that freshens the salty waters of the Dead Sea. The waters teem with life and all sorts of trees grow on the banks of this river providing fresh fruit monthly even as their leaves offer healing (Ezek 47.1-12; cf. Zech 14.8). The reference to “the tree of life” in John’s description borrows from Ezekiel’s vision but also alludes to “the tree of life” in the garden of Eden (Gen 2.8-9).

As we have seen, Jerusalem functions in the Revelation of John in three ways. First, the earthly Jerusalem is a “great city” destined for judgment. Gentiles will surround her and ultimately trample her for an appointed time determined by God. But unlike Babylon—the other “great city” in Revelation—God does not abandon her and will restore her (Rev 11.1-13; 20.1-10). Second, Mt. Zion and Jerusalem refer to the heavenly city where the Lamb and those who bear his and his Father’s name worship before the throne. These have remained pure and true despite threats and persecution (Rev 14.1-5; cf Heb 12.22). Finally, at the end of John’s visionary account, when the old order is eclipsed by a new heaven and new earth, the new Jerusalem comes down from God out of heaven. The entire city is construed in idyllic terms as an immense temple where God is immediately present with his people and where evil has been destroyed and impurity banished. In John’s apocalyptic imaginings, various lines of biblical prophecy find their fulfillment in the temple-city, configured ultimately as a new Eden (Rev 21.1—22.5).

Conclusion

The Gabriel Revelation and the Revelation of John are excellent examples of Jewish apocalyptic literature. As with other literature in this genre, they are written against the backdrop of persecution, martyrdom, and exile. Both attempt to comfort their communities with the promise that God is soon to act to rescue his suffering people (line 24; Rev 1.3; 22.20). Both depend heavily on earlier biblical prophecies and revelations.[33] Both describe Jerusalem as a great city whose destiny influences the future of the world (line 12; Rev 11.8; 21.10, 12, 16). Both envisage a great eschatological battle in which the nations of the world march against Jerusalem (lines 13-14; Rev 11.1-2; 20:7-10). In both accounts martyrs are many; but heaven answers, the Lord arrives,[34] and his arrival disrupts the natural course of events (lines 24-25; Rev 11.3-7; 11-13; 19.11-21). He comes with his holy angels (lines 26-29)—a vast angelic army (Rev 19.14)—to destroy evil and its representatives (line 20-22; Revelation 13; 20.7-10) and to establish righteousness. Ultimately, Jerusalem is restored and once again a great city (lines 32-33; Rev 21.1—22.5). Given the similarities found between these texts,[35] we may well be dealing with an eschatological scheme regarding Jerusalem that is current among certain apocalyptic Jewish and early Christian communities.[36]

Where these two apocalypses differ is in the nature of Jerusalem’s future. In contrast to Jerusalem’s destructions and falls in the past, The Gabriel Revelation envisages an earthly Jerusalem, attacked and yet, this time, miraculously rescued by God. John’s Revelation, on the other hand, finds ultimate hope in a new creation and a new Jerusalem that comes down from heaven. In John’s vision God is immediately present with his faithful people (including but especially the resurrected martyrs) in the temple-city.

John’s Revelation may also assist in interpreting obscure aspects of The Gabriel Revelation . In particular, Knohl reads lines 80-81 as Gabriel commanding the son of Joseph, “the prince of the princes,” to be raised from the dead on the third day after dying in battle. According to Knohl, the suffering of the “Messiah son of Joseph” is considered “a necessary stage in the redemptive process,” for his death moves God to come down at the Mount of Olives to avenge his suffering people.[37] If Knohl’s reading is correct, then the idea of a suffering-resurrected Messiah is earlier than Jesus and may have inspired the Nazarene carpenter to see his messianic vocation in terms of suffering and resurrection on the third day. But not all agree.

The book of Daniel and John’s Revelation offer a more appropriate context for how The Gabriel Revelation should be read at this point. Daniel envisions a day when a wicked king sets his heart against the covenant and its people (11.28). When his forces move south and are initially repulsed by the Kittim, the unnamed king (Antiochus IV) turns angrily against Jerusalem, profanes the temple, abolishes the sacrifices and sets up the abominating sacrilege (11.31). He is able to seduce some to his wicked ways, but those loyal to God and his covenant resist. “The wise,” as they are called, fall by the sword and flame; some are taken into captivity (11.33-35). But this suffering is portrayed as a refining, purifying event until the end. At the appointed time Michael, the great prince and protector of the people, arises and great tribulation proceeds (12.1). But Daniel is assured that his people—those whose names are found written in the book—will be delivered. The text concludes (12.2-3, NRSV):

Many of those who sleep in the dust of the earth shall awake, some to everlasting life, and some to shame and everlasting contempt. Those who are wise shall shine like the brightness of the sky, and those who lead many to righteousness, like the stars forever and ever.

This is the first clear reference to resurrection in the Hebrew Bible (cf. Isa 26.19; Ezekiel 37).[38] For our purposes, it is important to note that it does not refer to a single individual but to a group who have remained faithful unto death. Nickelsburg notes correctly that the period when Daniel was written was formative for Jewish views of the afterlife. The persecutions of Antiochus IV and the death of many hasidim created a theological problem: how can those obedient to Torah die such horrid deaths? The answer is resurrection.[39] Daniel underscores that the righteous martyrs will one day live and the wicked—often those who afflicted them—will be resurrected for eternal shame and punishment. Thus, God’s justice is satisfied.[40]

As we have seen the Revelation of John presents a scenario similar to what we find in Daniel (ch. 11). For a time Jerusalem and its temple are trampled by the nations. Resistance to the onslaught comes from the two witnesses—representatives of God’s loyal people—who bear witness to the one, true God and to whom God grants authority reminiscent of Moses and Elijah. Eventually, they too are captured and killed and their bodies lie unburied for three and one-half days in Jerusalem. But even as wickedness seems to triumph, God answers this injustice by resurrecting his two witnesses and assuming them up into heaven in full view of their terrified enemies. A great earthquake ensues, thousands are killed, and the survivors turn to give glory to the true God (Rev 11.1-13). In both Daniel and Revelation God’s faithfulness to his people and their vindication is demonstrated when they are raised from the dead. Resurrection here is not individual but corporate.[41]

If Knohl is correct in restoring the first part of line 80 as “By three days, live (חאיה), I Gabriel . . . “,[42] what is not clear is to whom does the angel speak. Knohl argues that he commands the fallen Messiah (“prince of the princes”), the earthly leader of God’s people to rise from the dead on the third day.[43] Thus, the resurrection of a single individual initiates the miraculous deliverance of Jerusalem and God’s people. But this interpretation is difficult to sustain in light of the fragmentary nature of the text and the more direct parallels we find in Daniel 11—12 and Revelation 11. In both cases, resurrection is not individual but corporate; it is God’s vindication of all his martyred faithful. Properly understood, the two witnesses in Revelation 11 are not individuals whom God resurrects after three and one-half days; they represent all believers who remain true to the end. If “live (חאיה)” is correct in line 80 of The Gabriel Revelation, it is more likely a command for all the martyred faithful to be resurrected on the third day (following Hos 6.2) even if it is expressed in a collective singular. The phrase “prince of the princes” in line 81 then is not the one addressed and therefore raised from the dead but the one who raises the dead, namely, God (cf. Dan 8.11, 24-25). This may well be confirmed by line 85 which reads: “then you [plural] will stand (אז תעמדו) . . .” The verb עמד (“stand”) is used to refer to future resurrection in Dan 12.13 and Ezek 37.10. If this interpretation is correct, line 85 then refers to the resurrection of God’s martyrs in a not-too-distant future.

The Gabriel Revelation, the Revelation of John, Zechariah 14, and Daniel 11—12 depict what may be variant versions of an accepted apocalyptic scenario regarding the future of Jerusalem. In the past the holy city had fallen to the might and cruelty of various empires. But in the future, when all the nations of the world line up against her for one, final battle, the God of hosts will intervene decisively and reverse the shame of the past. Whether by resurrection, some miraculous incursion, or new creation, heaven will guarantee that Jerusalem will once again be the center of the world and her loyal citizens will rest safe in God’s glorious presence.

[1] Pliny the Elder (Natural History 5.14) remarked that Jerusalem was one of the most well known and significant cities in the east.

[2] Carey Newman, “Jerusalem,” Dictionary of the Later New Testament and Its Developments, ed. Ralph Martin and Peter Davids (Downers Grove: InterVarsity, 1997), 561.

[3] A. F. J. Klijn, “2 (Syriac Apocalypse of) Baruch,” The Old Testament Pseudepigrapha, vol. 1, ed. James H. Charlesworth (Garden City, NY: Doubleday, 1983).

[4] Philip King, “Jerusalem,” Anchor Bible Dictionary, 3:747-766.

[5] Adela Y. Collins, “The Dream of a New Jerusalem at Qumran,” in The Bible and the Dead Sea Scrolls, ed. James H. Charlesworth, vol 3: The Scrolls and Christian Origins (Waco, TX: Baylor University Press, 2006), 238.

[6] Florentino García Martínez and Eibert J. C. Tigchelaar, ed. The Dead Sea Scrolls: Study Edition. Volume 1. Leiden: Brill, 1997.

[7] Jerome Murphy-O’Connor, “Jerusalem,” in Encyclopedia of the Dead Sea Scrolls, vol. 1 (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2000), 402-4.

[8] Ada Yardeni and Benyamin Elitzur, “Document: A First Century BCE Prophetic Text Written on a Stone: First Publication,” [In Hebrew] Cathedra 123 (2007): 155-66.

[9] Ada Yardeni and Binyamin Elizur, “A Hebrew Prophetic Text on Stone from the Early Herodian Period: A Preliminary Report,” Cathedra 123 (2007), 55-66 [Hebrew]; Israel Knohl, Messiahs and Resurrection in The Gabriel Revelation (London and New York: Continuum, 2009), 1-7.

[10] Elisha Qimron and Eliyahu Yuditsky, “Notes on the So-Called ‘Gabriel Vision’ Inscription,” Cathedra 133 (2009), 133-44 [Hebrew].

[11] Knohl, Messiahs and Resurrection, restores “Son of David” in line 8. “Son of David” is taken as a messianic title in Ps Sol 17.21 and Matt 9.27.

[12] Knohl, Messiahs and Resurrection, xii.

[13] Josephus Wars 2.1.1 – 2.5.-5; Antiquities 17.10.8-10.

[14] Based on the poor preservation of the text, this seems the case.

[15] Knohl, Messiahs and Resurrection, 9.

[16] A connection made by the writer of Hebrews (12.25-27).

[17] Qimron/Yuditzsky and Yardeni/Elitzur read “place” (מקומו) at the beginning of line 24 while Knohl reads “seat” (מושׁבו).

[18] So Knohl, Yardeni and Elitzur. Qimron and Yuditzsky restore this as “the God of the chariots will listen to the [cr]y of Jerusalem and will console the cities of Judah . . . “

[19] Knohl, Messiahs and Resurrection, 17.

[20] Yardeni and Elitzur, 6.

[21] Alternatively—as with the Qumran sectarians and early Christians (e.g., Matthew 21—25; Gal 4.21-31)—exile from Jerusalem and the temple may be self- imposed based upon a negative evaluation of the current temple and its leadership.

[22] Yardeni and Elitzur, 10.

[23] Knohl, Messiahs and Resurrection, 21.

[24] Knohl, Messiahs and Resurrection, 12, argues that the “wicked branch” is “a wicked messianic king, a precursor to what would subsequently be termed the Antichrist.” “Branch” may well be used here with messianic import. Jeremiah envisioned a day when the Lord will raise up a “righteous branch” for David. He will reign with integrity and wisdom and his name will be “The Lord is our righteousness” (Jer 23.5; cf. Isa 11.1-3; Matt 2.23).

[25] Carey Newman, “Jerusalem,” Dictionary of the Later New Testament and Its Developments, ed. Ralph Martin and Peter Davids (Downers Grove, IL: InterVarsity, 1997), 564.

[26] All translations of Revelation are my own.

[27] The predications at the beginning of this and other letters should be read christologically.

[28] Adela Y. Collins, “The Dream of a New Jerusalem at Qumran,” in The Bible and the Dead Sea Scrolls, ed. James H. Charlesworth, vol 3: The Scrolls and Christian Origins (Waco, TX: Baylor University Press, 2006), 252.

[29] The word translated “measure” (μέτρησον) can also mean “count.”

[30] For a description of the Zion tradition see J. J. M. Roberts, “The Davidic Origin of the Zion Tradition,” JBL 92 (1973): 329-344.

[31] Adela Y. Collins, “The Dream of a New Jerusalem at Qumran,” in The Bible and the Dead Sea Scrolls, ed. James H. Charlesworth, vol 3: The Scrolls and Christian Origins (Waco, TX: Baylor University Press, 2006), 253.

The four walls of the new Jerusalem are measured to be about seventy-five meters high. They surround a city made of gold and yet clear as glass. The city walls are founded and ornamented with precious jewels. The description here of the new Jerusalem in Revelation is similar to the Description of the New Jerusalem (5Q15 [5QNew Jerusalem]) found in the Dead Sea Scrolls. Isaiah’s prophecy (54.11-12) may have inspired such apocalyptic imaginations.

[32] Ibid.

[33] In a similar way 1 Macc 7.16-18 describes the massacre of a group of scribes by Alcimus and Bacchides as fulfilling Ps 79.2-3.

[34] In Revelation the rider on the white horse bears the names: “The Word of God,” “King of kings,” and “Lord of lords” (19.11-16). Within the narrative vision, this can be none other than the risen Jesus.

[35] Also with Zechariah 14 and Daniel 11—12.

[36] Compare the role of Jerusalem in the eschatological discourse in the Synoptic Gospels (Matt 24.1-36; Mark 13.1-37; Luke 21.5-36).

[37] Knohl, Messiahs and Resurrection, xii-xiii.

[38] When 4 Maccabees is written, Ezekiel 37 is being read as a promise of bodily resurrection for those who do the will of God (18.16-19).

[39] W. E. Nickelsburg, Resurrection, Immortality, and Eternal Life in Intertestamental Judaism and Early Christianity (Cambridge: Harvard Divinity School, 2006), 33-53.

[40] These convictions are worked out narratively in the celebrated account of the seven brothers and their mother (2 Maccabees 7). The devout family is captured by Antiochus IV, forced to eat pork, and afflicted with torture. Despite threats of dismemberment and death, all the brothers pledge fidelity to God and his law. One-by-one they are killed as their pious mother looks on, each expressing confidence that the true king of the world will raise them to eternal life (see 4 Macc 17.5).

[41] There is little in the vision recorded in Revelation 11 that is distinctively “Christian.” Unlike, for example, Paul who links the resurrection of believers directly to the resurrection of Jesus (e.g., 1 Thess 4.13-18; 1 Cor 15.20-28), the account in Revelation 11 does not. In fact, Rev 11.1-13 could have been written by any apocalyptically-minded Jew in the late second temple era (cf. Daniel 11—12; Zechariah 14; The Gabriel Revelation).

[42] Not all agree, of course. Qimron and Yuditsky read the word as “the sign” (האות). Likewise Ronald Hendel, “Simply `Sign’,” Biblical Archaeology Review 35 (2009), 8. Matthias Henze also expressed doubt in his SBL Seminar presentation (November 22, 2009) “The Gabriel Revelation Reconsidered: A Response to Israel Knohl.”

[43] Knohl, Messiahs and Resurrection, 26-28. bases his decision in large part on his reading of Daniel 8.

[w1]I presume this sentence is referring to Revelations 11:1. Here the Greek word stem is metreo. It appears here in the form μετρησον.

Leave a comment