I remember my fourth grade teacher, Mrs. Potts, opening a vein when anyone wrote “Xmas” instead of “Christmas.” She felt there was a war on Christmas and that people who abbreviated the name of the holiday were trying to take Christ out of Christmas. I suppose that is true for some people, but when you look into the real story of “Xmas” you realize that something else is at work.

The story begins with the Ten Commandments. One of those commandments says, “Do not take the name of the LORD in vain.” The name by the way is not “LORD,” that was a respectful translation or substitute for the name. In Hebrew THE NAME is four letters, yodh-he-vav-he. The technical term for the name is the tetragrammaton (literally, “the four letters”). Scholars today think the name may have been pronounced—when it was pronounced—Yahweh or Yahveh. But we aren’t sure. This was the covenant name of God, the name revealed to Moses and Israel at Mt. Sinai.

Under the influence of the commandment about the misuse of God’s name, the faithful spoke it less and less. By the time of Jesus speaking the name was considered blasphemous in almost every circumstance. The rabbis made their mark by building a hedge about the law. If you never spoke God’s name, you could never be guilty of taking the name in vain. It was a way of safeguarding the name. Even when reading Scripture in the synagogue, a substitute word was used. In Aramaic-speaking synagogues the readers said “Adonai.” In Greek-speaking synagogues they said “kyrios.” Both mean something like “Lord” or “Master.”

The Dead Sea Scrolls provide good evidence for how the name of God was written in the centuries and decades leading up to the New Testament era. In many of the biblical scrolls the name of God is written in paleo-Hebrew script. That would be like shifting to a Gothic font when writing the name of God. In other scrolls the name is not written at all; it is represented by four, thick dots written in the center of the line. In yet other scrolls where the name of God should be there is a blank in the line just large enough for the tetragrammaton. Scholars theorize that the blank was left by a junior scribe and would have been filled in later by a senior scribe who had permission to write the name. Where there is a blank in the line, we think the senior scholar never got around to writing the divine name in the blank. These were some of the ways the faithful showed respect for the name of God.

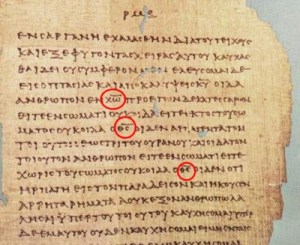

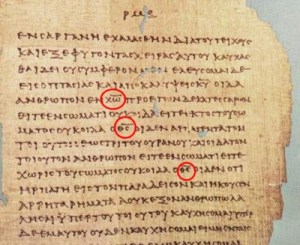

Early Christians developed their own way of signaling respect for the names and titles associated with God the Father, God the Son, and God the Holy Spirit. Copying the New Testament books in Greek, they abbreviated the names (usually first letter and last letter) and placed a line above those letters. You can see this in the picture. Scholars refer to these as nomina sacra (Latin for “sacred names”). Copyists continued to write sacred names this way for centuries. It remains a common practice still among artists who create the icons used in the eastern churches. Many names and titles were written this way including “God,” “Father,” “Jesus,” “Son of God,” “Son of Man,” “Christ,” “Lord,” “Holy Spirit.” For our purposes note the nomen sacrum for “Christ;” it was written XC. Now remember these are letters from the Greek alphabet not our Latinized version. It is not “X” (eks) the 24th letter of our English alphabet but the Greek letter “Chi,” the first letter of the title “Christ.”

Earliest versions of writing Christmas as “Xmas” in English go back to the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle (about 1100). This predates the rise of secularism by over 600 years. The Oxford English Dictionary cites the use of “X-“ for “Christ” as early as 1485. In one manuscript (1551) Christmas is written as “X’temmas.” English writers from Lord Byron (1811) to Samuel Coleridge (1801) to Lewis Carroll (1864) used the spelling we are familiar with today, “Xmas.”

The origin of “Xmas” does not lie in secularists who are trying to take Christ out of Christmas, but in ancient scribal practices adopted to safeguard the divine name and signal respect for it. The “X” in “Xmas” is not the English letter (eks) as in “X marks the spot,” but it is the initial Greek letter “Chi” (X), the first letter of the title “Christ.” No doubt some people today use the abbreviated form to disregard the Christian focus of the holy-day, but the background tells a different story, a story of faithful men and women showing the deep respect they have for Jesus at this time of year.

Merry Christmas or should I say “Merry Xmas”!

You must be logged in to post a comment.