The Philippian Hymn–Phil 2.5-11

For Paul, the story of Jesus provided the greatest example of what this humility looked like when it was embodied in a life. He found that story told powerfully and succinctly in an early Christian hymn. No other passage in the NT has been studied more thoroughly.[1] Given the poetic, parallel structures and its unusual wording, the hymn was likely a preformed tradition that Paul incorporated into his letter. Exactly who wrote it, for whom and when are questions worthy of speculation but unlikely to bring certainty. The fact that Paul included this preformed tradition in his letter to the Philippians indicates his complete agreement with its theology. Even if Paul didn’t write it, he did agree with it.

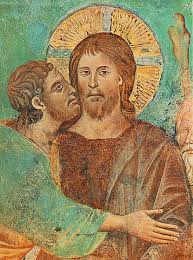

Paul earnestly desired for the “mind” of Christ to shape the lives and community in Philippi. He sets up Jesus as the lordly example of humility and selfless service. The hymn is constructed around two movements: (1) the descent (katabasis) from equality with God to the humiliation of the cross and (2) the ascent (anabasis) from death to exaltation/ resurrection by God and universal acclamation by all creatures. The descent can be graphically portrayed (2:6-8):

Though he was in the form of God

He did not consider equality with God as something to be grasped

He emptied himself

Taking the form of a servant

Becoming in the likeness of men

Being found in form as a man

He humbled himself

Becoming obedient to death

Even death on a cross

Likewise the ascent (2:9-11)

To the glory of God, the Father

“Jesus Christ is Lord”

Every tongue confess that

(of heavenly, earthly and subterranean beings)

Every knee shall bow

So at the name that belongs to Jesus

And bestowed on him the name above every name

Therefore God highly exalted him

There are a number of interpretive schemes for unraveling the meaning of this hymn. James Dunn notices the number and the sequence of Scriptural allusions to Adam and concludes that the Christ hymn in Philippians 2 is “the fullest expression of Adam Christology in the NT” (cf. Heb 2:5-9).[2] In particular he notes that Adam is made in image of God (cf. Gen 1:27) and is tempted to grasp at equality with God (cf. Gen 3:5). The first man fails, of course, and becomes an obedient slave to corruption and death. Ultimately, in Jewish tradition Adam is glorified. For Dunn and other interpreters, Jesus provides the converse of Adam, particularly in that the second Adam did not try to grasp for equality with God (something He did not have). Rather He emptied himself and humbled himself by being willing to die a criminal’s death on the cross. Given other Adam-Christ typologies in Paul, there may well be a subtle allusion to Jesus as a new Adam who reverses the curse of Adam’s sin. But this does not cover the interpretive canvas.

Michael Gorman suggests that the humiliation-exaltation pattern in the hymn is based upon a similar pattern found in the fourth servant song (Isa 52:13—53:12). Although he does not discount other options, he believes the Christ hymn would have been patterned after and read according to the final servant poem augmented by Isa 45:23. Isaiah’s servant song depicts the Servant of YHWH

- exalted and lifted up (Isa 52:13)

- despised and reject (53:3)

- pierced for our transgressions (53:4)

- led like a lamb to the slaughter (53:7)

- cut off from the living (53:8)

- he will see light (53:10)[3]

- God allots him a portion with the great (53:12)

The humiliation and exaltation pattern in the fourth Servant poem does appear to provide further background for understanding the model for the Christ hymn.

One of the important interpretive questions we find in the text has to do with the meaning of the phrases “existing in the form of God” and “did not consider equality with God as something to be grasped.” Most scholars take these as a reference to the preexistence of Christ. Prior to his entrance into the world, he existed in the form of God. Nevertheless, he decided not to hold onto his equality with God. Instead he emptied himself and became a human being. According to this construal, the hymn is a statement of the preexistence and incarnation of Christ, a divine person. But not all agree that the doctrine of the preexistence of Christ occurs so early. As we have seen, Dunn interprets this as an allusion to Adam made in God’s image (Gen 1:27) and seeking to become “like God” by eating the fruit of the tree of the knowledge of good and evil (Gen 3:5). Accordingly, these phrases should not be read as referring to the preexistence or incarnation of Christ.

Again, while a subtle allusion to Adam is possible, some form of preexistence is clearly in view from one who was in the form of God and who became man. If he had to become “man,” he was not “man” before. There is no reason to conclude the Christ hymn does not assume the preexistence of a divine being who subsequently became the man we know by the name “Jesus.” Yet the hymn is silent on the salient points we are interested in. Some have tried to flesh out the extent of the self-emptying by naming which attributes he gave up on his journey toward the cross. But this is more reading into (eisegesis) than reading from (exegesis) the text. At the end of the day the decision to lay aside equality, empty himself and humble himself had only one thing in view: the cross.

As a result of his faith obedience, God super-exalted the crucified Jesus and gave him the name above every name (2:9). Some, inspired more by our hymnody and praise choruses than Scripture, have wrongly concluded that “the name above every name” is the name “Jesus.” But Jesus was a common name then and now. It can hardly be a candidate for the name above every name. The genitive case “Jesus” in 2:10 is best taken as a possessive genitive, i.e., at the name that belongs to Jesus. Three things are certain about the “name”: (a) it is a name bestowed upon him in the exaltation-resurrection; (b) it is a name above every name; and (c) it is a name that belongs to Jesus. So what is the name? Given all we know from the hymn and given the reverence accorded the name of God in Hebrew Scriptures, the name must be LORD (kyrios), God’s holy, unspeakable name (Hebrew, YHWH). In the Greek translation of the Hebrew Bible, kyrios (translated “Lord” in most versions) consistently renders the divine name, a name so holy it was protected by one of the ten commandments (Exod 20:7). This conclusion is assured by the universal acclamation of all heavenly, earthly, and subterranean creatures. When the name that belongs to Jesus is expressed: “every knee will bow, every tongue will confess, Jesus Christ is Lord” (2:10-11, alluding to Isa 45:23). These phrases belong to one of the most significant monotheistic passages in the Old Testament and refer originally to the worship of YHWH.[4] Paul has deliberately taken scriptural language regarding the veneration of Israel’s one God and applied it to the risen Jesus. This is a remarkable appropriation of God’s name and worship addressed to Jesus. As Larry Kreitzer noted: “it is difficult to imagine any first-century Jew or Christian even remotely familiar with Isa. 45 hearing this final stanza of Phil 2.9-11 without recognizing that words of theistic import have now been applied to Jesus.”[5] Despite this, for Paul, the unique identity of God, including his name, and his exclusive right to worship are not threatened by the universal acclamation of Jesus as “Lord.” Since the Father has bestowed upon the crucified Jesus His name, the apostle understood that the worship of Jesus by all creatures brought glory to God and fulfilled His will.

You must be logged in to post a comment.